I’m sitting on a porch with my dad. He’s having trouble with his phone, and I’m trying to help him when he says, “My phone is three dimensions ahead.”

I’m used to these sorts of things from him… so I roll with it. “Oh, we can change that in the settings.”

Before a few years ago, Dad was a university professor and a research biologist. He was a smart guy, and by all reports a good teacher too. And he’d been a good father. Involved. He coached my soccer team and helped me with science fair projects. He and Mom took the family on trips to see wonders like the Grand Canyon, Yellowstone, and the Smithsonian. We camped a lot, and I loved it.

Dad taught me how to learn, and that is one of the greatest gifts anyone can give to someone.

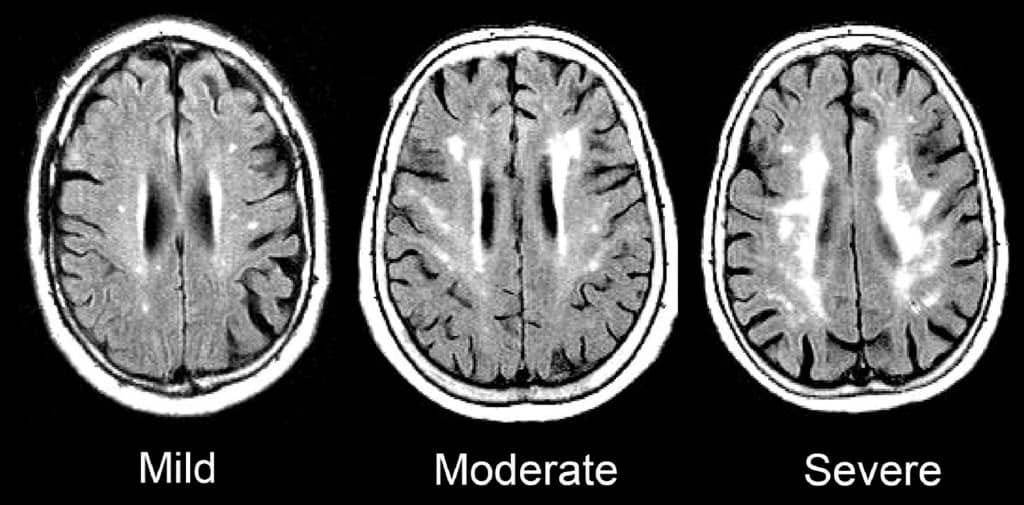

Dad is different now. He has dementia—a severe form of white matter disease. Sections of his brain’s white matter have become dead zones. In his case, the cause could have been head trauma he suffered a few years ago or possibly a series of micro-strokes. The disease affects his short-term memory in strange ways, but more significantly, it affects his perception of reality.

Dad can’t be sure what is real now, what was real moments ago, and he definitely can’t do what our brains are usually so very good at—making predictions of what will happen next. A healthy brain is a prediction machine; our actual perception of the world is generated by our own brain first, then modified if the sensory input doesn’t match the prediction.

During normal, everyday life, you and I take for granted that what we see and hear and feel is objective reality. Oh, we might entertain theories of multiple dimensions and universes splitting off at every decision point. But our brains haven’t evolved to actually perceive the world that way.

In daily life, we believe in the constancy of the external world. We presume that cause and effect is a basic tenet of existence and that the universe persists even when we’re not actively looking at it. We trust that reality generally operates according to basic rules; it is fundamental to our sanity.

Dad’s disease has taken that trust away.

“Oh no! It’s a new iteration.”

For example, when a man walks by where I’m sitting with Dad and greets us with a “Good afternoon,” I return the greeting, but Dad ignores him. I ask Dad why he didn’t say hello, and he shrugs and says matter-of-factly, “He’s from a different day.”

Later, we leave the porch and enter his apartment. I close the door behind us. So far, so good. Until we open the door to walk back outside, and Dad says, “Oh no! It’s a new iteration.”

We had just been here a few minutes earlier, and to me, the porch looks exactly the same. To Dad, it’s a new reality. A different version of existence. His malfunctioning brain makes it so that he’s never certain about what to expect. He cannot trust his own perceptions.

“He’s from a different day.”

Dad’s malfunctioning brain makes him an unreliable narrator of his own experiences. An unreliable narrator in fiction is when the reader can’t trust what the narrator is telling them. Some of the more famous examples include Fight Club by Chuck Palahniuk and Memento (the movie) by Christopher Nolan.

This way of storytelling pulls the rug out from under the reader’s feet, putting into doubt what we thought has been happening all along in the story. And the same thing is happening to Dad many times a day. The lack of a solid cognitive foundation of reality is hard for him. He takes meds for anxiety and blood pressure and still he struggles. It’s very real for him.

Brains are not completely reliable narrators at every stage of life, but they get more unreliable as we age. As I’ve aged, my own capacity to remember has eroded too. Gone are the days that I could learn organic chemistry by the rote memorization of thousands of reactions. And it’s not just memory formation; my brain no longer clicks along on all cylinders all the time.

It’s ironic; I know and understand so much more than I did when I was younger, but I can’t think as quickly. Can’t share and use the knowledge in the same way I could have when my brain was more flexible and agile.

More and more, I enter a room and forget what I came for. More and more, I need written lists to keep track of things. I know I’m not alone in this; a lot of people experience cognitive slow down and memory recall issues as they get older.

But it’s frustrating and sad that it’s getting worse as I get older. I mean, I hope I have quite a few years of intelligence left, but there’s no way to predict. And memories; I don’t want to lose any more of those.

I can’t help but wonder if I’m on the same path as Dad, just a couple decades or so behind him. If I, too, am Charlie from Flowers for Algernon—that maybe we are all on a very slow version of the same arc. That maybe dementia is a continuum that we’re all moving along with the passing of time.

“My phone is three dimensions ahead.”

Dad was always so proud of his intelligence. He’s still smart in the intermittent moments between reality resets. And it’s in these pockets of lucidity that I see the person he used to be—the man I remember. So many great times. He was a good father, a patient mentor, and ultimately a trusted friend.

Most of the time, though, Dad is a different person now. And I do genuinely like the person he has become. But it’s the man he was—the intelligent, caring, engaged father who I loved and who I miss. I grieve for the loss of that version of him.

That Dad was from a different day. That Dad was an earlier iteration. And as much as I wish things were different, we’re now three dimensions ahead with no way back.

My dad had been a rocket scientist (literally—chief of man-machine controls at NASA HQ), and he got dementia at 80. The best thing I can say about his particular disease was that he was always aware that he had it. "Your mother says I can't remember anything," he told me, "And, mostly, she's right!"

That was lovely, Jak. I have always loved (and been somewhat intimidated by) your dad. He took care of my sister when she was in college. He was always a good friend and mentor. I will never forget how he helped me my senior year in highschool with a science experiment that won me third place in state. He let me use his spectrophotometer to test the UV resistance of different sunscreens. Until then, I hated science. Still don't love it, but because of his help, I got an A in my physics class. 35 years later, I remember it. People touch others' lives in profound ways they may not even realize. Your dad was one of those people, and I don't know that he ever realized how special he is.